The Art Collector and the Tax Deal

Douglas Duncan was a pioneering Canadian art dealer and ambitiously hapless businessman. Known as the dealer and artistic executor of artist David B. Milne, he was legendary for his unopened mail, uncashed cheques and, yes, of course, failure to write a will. Prior to his death in 1968, he expressed a wish that his large art collection go to public galleries. His long-suffering sister and legal heir, Frances Barwick, was left to untangle the mess. Good thing it was a different time and Revenue Canada was willing to be pragmatic in the national interest.

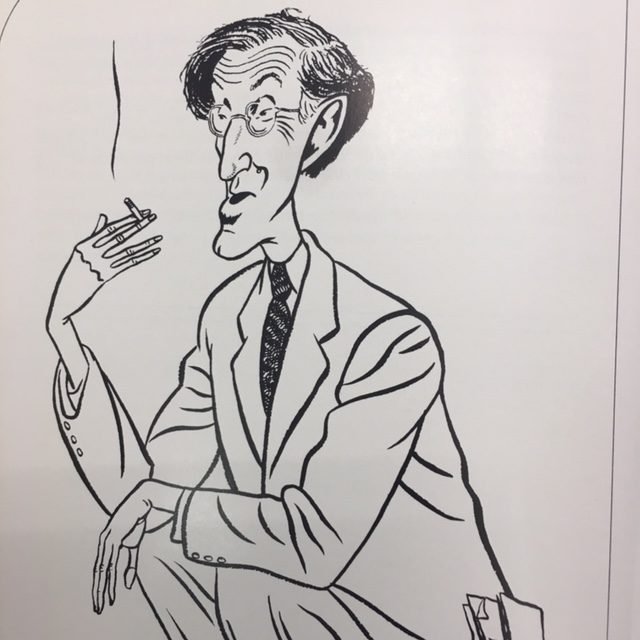

The Man

A 1953 caricature of Douglas M. Duncan by Alan Reeve. Note the envelopes in his pocket at the lower right.

Douglas M. Duncan (1902-1968) was the dreamy, artistic son of a pulp and paper CEO. He grew up in Forest Hill, Toronto, and only moved out of the family home at the end of this life. Trained in Europe as a bookbinder, he co-founded The Picture Loan Society at 3 St Charles St. in 1936. The Society, which both sold and rented art by the month, aspired “to encourage the fresher element in Canadian art.” Over the next 32 years, Duncan was unfailingly supportive of artists such as Milne, Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald, and Carl Schaefer. The support often came in the form of self-subsidy of the Picture Loan Society, as Duncan assembled a large personal collection, which filled his home and business.

I first heard of Duncan through a client who had bought some Milne dry points in the 1960s from The Picture Loan Society at $60 each. He said the gallery was a friendly mess, and at the back a locked office was swamped in paper. When Duncan died, the client was contacted by the Canada Permanent Trust Company and asked to provide proof of payment for the Milnes. Duncan sold art, but he couldn’t be bothered to cash cheques.

His Estate

Duncan died gay and childless with a will from 1935, which was before he caught the art bug. His estate would have been subject to significant estate taxes, which were levied at almost 50% of estate value. But those were the days when the Government of Canada, through Canada Customs and Revenue Agency, had discretion about how tax law would be applied. The Duncan collection was probably the largest and deepest collection of Canadian art ever assembled at the time. It had cultural value to the nation that exceeded the tax revenue. A deal was reached.

Frances Duncan Barwick arranged the donation of over 4000 paintings, prints, and drawings to 44 Canadian galleries, which must have been every gallery in Canada at the time. The National Gallery of Canada received 634 works, which were toured 13 communities, in 1971-72. To this day, it is an unprecedented donation, and it couldn’t happen with current tax law.

The “No Deal” Present

I have been told that the current philosophy for the Income Tax Act (Canada) at the Department of Finance is to reduce or remove administrative discretion in the tax system. Tax rules are intended to be clear and precise. But audacious discretion played a role in the recent past. There were other “big vision” deals involving significant estates at the time. In 1957, the Canadian Government of Canada used $50 million in tax revenue from the estates of Sir James Dunn and Izaak Walton Killam to endow the Canada Council for the Arts. It was an act of nation building that turned taxpayers into donors.